Where are we going?: Navigating the road to autonomous vehicles

$106B spent on AV since 2009, and we're all still driving ourselves. Where has that money gone? Will it all be worth it? What is the end goal?

Overview

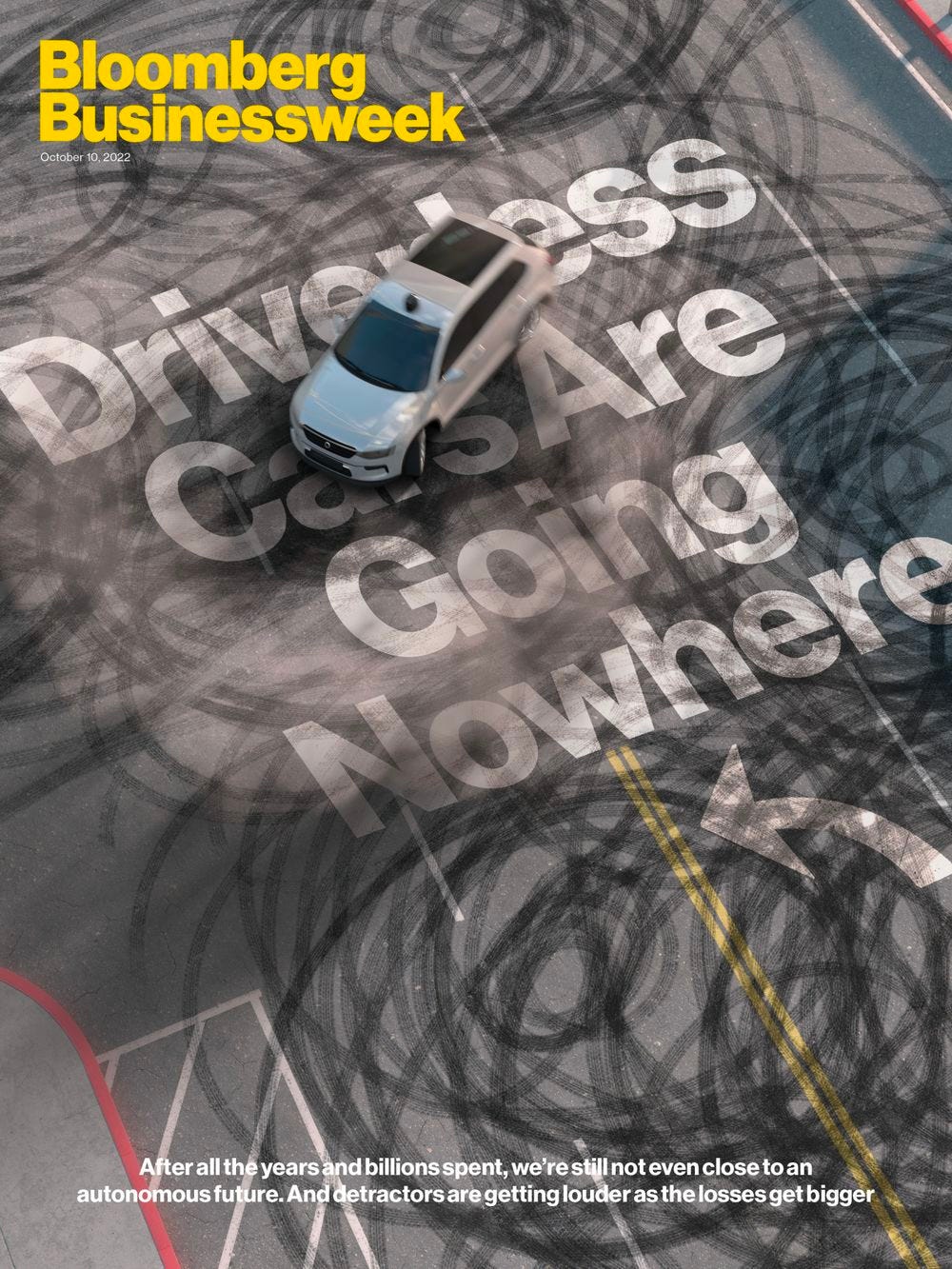

The October 10 Businessweek cover story reported that in spite of $106B spent by multiple companies, autonomous vehicles (AV) were still far from the promised vision. In this week’s post I’ll cover the following:

The Chassis – Context on AV

It is tough to estimate the market – but it is massive. Car sales alone are a $5T industry globally. But there are other industries that will be replaced or created. Freight is $3T, and Cathie Wood estimated robotaxis will be $11T+. Combined, that would make it nearly the size of the entire US economy. There is also hope that it could replace logistics (i.e., Amazon).

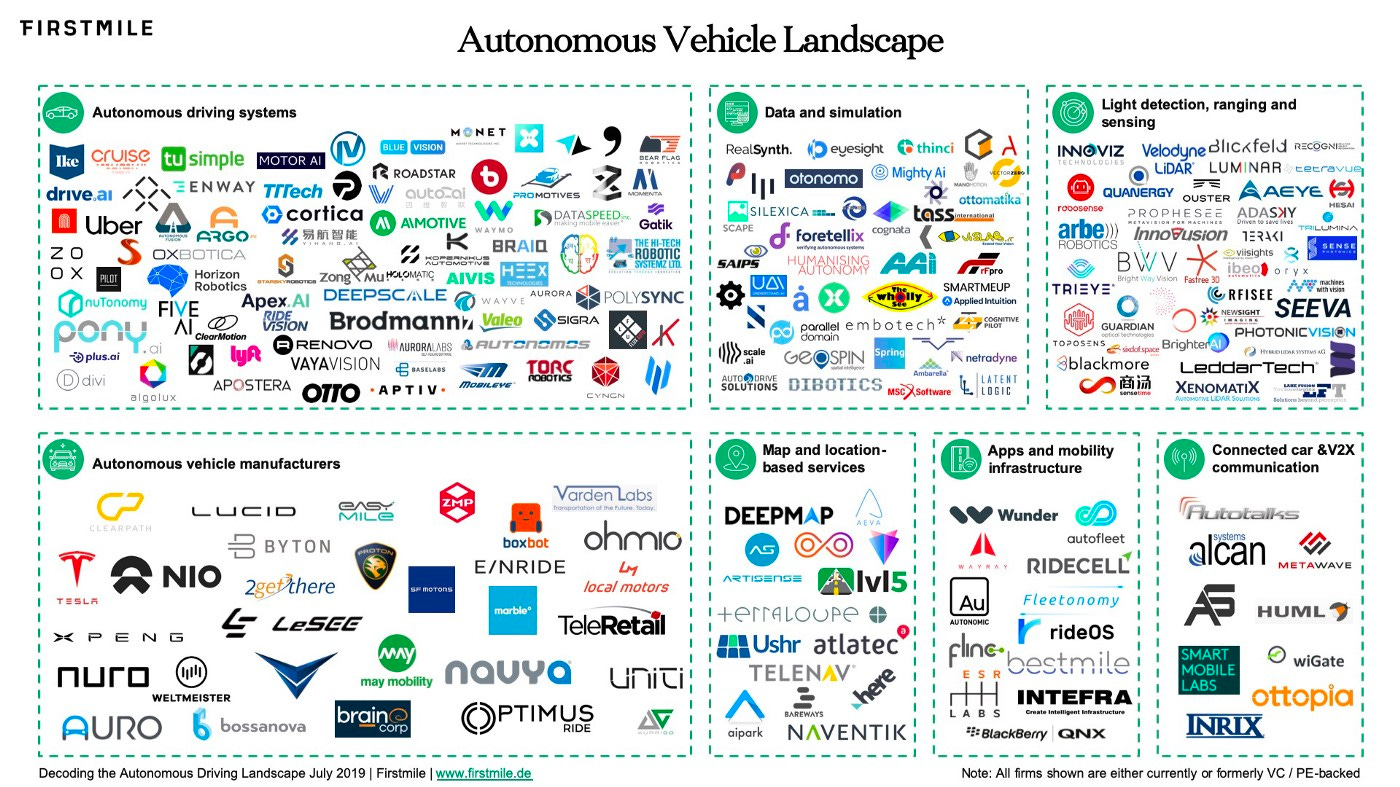

The carmakers need to defend their market; tech companies want to enter it. It seems crazy for Alphabet and Apple to go after something so far afield, but whatever the size of AV, it is significantly larger than digital advertising ($600B) or consumer electronics ($850B). Major players include:

The car makers – Basically all of them, leaders include: GM/Cruise, Volkswagen, Tesla

Big Tech – Alphabet/Waymo focuses on the AV system and not car manufacturing; Apple, Baidu, Amazon/Zoox may do both

Ride hailing – Didi; Uber and Lyft sold their divisions

They’ve been at it a long time to still be pre-revenue, almost certainly a record for a new product launch. The first commercial airline flew 11 years after the Wright Flyer!

Timeline

1986 – Carnegie Mellon (with DARPA help) builds Navlab 1, its first computer-driven car

2008 – Anthony Levandowski’s first public demo

2009 – Google/Levandowski start Waymo as a secret project

2013 – First street test drive

2015 – Robotaxis start testing

2017 – Waymo launched self-driving rides (with a human) in Phoenix

2022 – Driverless taxis approved for Cruise in SF and Baidu in Wuhan

Some of the unfulfilled promises sound like Theranos – always “just around the bend”. Waymo was telling new employees in 2017 that it was 18 months away from significant expansion. In 2018, the company signed up for 80,000 Jaguars and Chryslers; deliveries have been “far fewer”. In 2019, Elon said Tesla could have a robotaxi fleet by 2021.

Article Summary

The $106B estimated spend comes from a 2021 McKinsey report.1 Businessweek’s Max Chafkin asks what that money – and the sweat of our generation’s best, brightest, and richest – has bought us.

The quotes are damning:

“You’d be hard-pressed to find another industry that’s invested so many dollars in R&D and that has delivered so little…It’s an illusion.” (Anthony Levandowski, Godfather of AV)2

“It’s a scam.” (George Hotz, founder of driver-assistance system company turned Twitter intern)

“Long term, I think we will have autonomous vehicles that you and I can buy…But we’re going to be old.” (Gartner analyst)

The article cites only those three sources, and it is difficult to square their statements with the growing prevalence of driverless taxis on our streets (if you live in a few cities).

However, there are some other indicators from within the industry:

In 2018, analysts valued Waymo as much as $175B; 2021 funding was at $30B.

Waymo had a mass exodus of top talent recently, including the CEO, CFO, and several division heads.

Uber shut down Otto in 2018 and sold the robotaxi business to Aurora in 2020.

Zoox was sold to Amazon for $1.2B in 2020; it had raised $1B.

Apple’s Project Titan head left for Ford; team is reportedly demoralized.

Aurora’s stock is down 93%, at $1.4B market cap.

Other companies have folded, including Argo AI (raised $3.2B from Ford/VW/others) and Embark trucks (nearly SPAC’d at $5B this summer).

Computers are better than humans at chess and spaceflight – what’s so hard about driving?

The demos we’ve seen are mostly controlled environments. The challenges come from so-called “edge cases” – which are actually so common you couldn’t drive a few miles without encountering one:

Unusual Obstacles – AVs don’t know a flock of pigeons will fly away so they stop 20 yards away.

Non-AV Humans – How should they react to an aggressive driver cutting across three lanes? Someone at a four-way stop gesturing to you to go ahead? A bicyclist weaving through traffic?

Turning Left – Navigating oncoming traffic is tricky for humans; for AV it’s like pole vaulting.

Weather – Hence the testing in Arizona, California, and Texas

The cars you see on the road still rely on humans to navigate the edge cases (in person or remotely). The companies believe that with enough human correction, the cars will learn to recognize the patterns through “deep learning” (read: memorization). But the scenarios are too different for the knowledge to be transferable.

Pushing back: What’s that? An exaggerated headline?? That would be headline-making news!

While the article claims the industry is “going nowhere”, the experts acknowledge we will ultimately achieve the vision – but it will be a long time. Still, all of this could be moot if it becomes the $20T industry evangelists hope it will be.

Case for hope

To understand the “What You Need to Believe” case, I looked at the 2018 Morgan Stanley report valuing Waymo at $175B. Here is how they (Brian Nowak) get there:

$80B, Robotaxi – Charge $0.90/mile, 4% of global miles 2040, 12% long-term margins

$90B, Logistics – 8% of global freight by 2040

$7B, Licensing – Sell capability to OEMs/car makers

$?, Other – UPS/Fedex, retail/Amazon, REITs (save on parking space)…This is such a big opportunity, replacing $1T Amazon isn’t worth quantifying.

I don’t think that’s crazy. Who knows the economics – but 4% of miles and 8% of freight in two decades could be achievable for a massive industry-shakeup by a massive company’s subsidiary. Tough to find precedents, but Tesla, after 18 years, reached 2.4% of US car sales. And miles should scale disproportionately for robotaxis/freight: Uber/Lyft drove 20% of miles in SF in 2017.

To test an extreme downside case, I took that same forecast, assumed it started today, and then delayed it a decade: Assume the business breaks even 2026-2036 and then grows at the same 38% CAGR until 2055.

Even in my downside case, Waymo would still be worth $61.7B today and give Alphabet a 14.1% IRR from its 2009 launch.3

In short, if you believe AV is going to be a massive industry in my lifetime, it is still worth a lot today – even pre-revenue.

Takeaway: For investors, who know it best, to value Waymo at $30B last year, things must be going terribly wrong.

Here is what their model might have looked like — taking my downside case and haircutting profits 50% (without changing burn) gets to $31B NPV and 11.5% IRR. That is getting hard to justify — without accounting for market performance since June 2021.

Maybe this is just Waymo. But given the other indicators that they are still among the leaders and that competitors are feeling similar struggles, it is likely indicative of the industry.

Like the British with cars, I’ll take the opposite side

The AV companies tout their (potential) safety. But there are two issues with that value proposition.

First, the Businessweek article quotes an AV exec who states, “Humans are really, really good drivers—absurdly good”. A lot of accidents come from recklessness, which we could address in other ways. (Bus drivers are 5x safer – let’s all drive like we have kids onboard.)

Despite Waymo’s claims, Chafkin argues there is not enough data. One person dies for every 100M miles driven in the US; Waymo has driven a cumulative 20M miles over 10 years.

Second, people (at least Americans, other than Shira Ovide) don’t care.

I once heard Marc Andreessen say that if the car were invented today, the US government would shut it down: millions of people (teenagers!) driving at instant-death speeds towards each other with just a few feet between them or people biking and walking.4

Consider how cities have responded to non-lethal threats like electric scooters, Uber, and Airbnb!

Unlike shark attacks, which we go to irrational ends to prevent – we accept the risk of car accidents. We had 43,000 car deaths last year – almost exactly the same as 45,000 gun deaths in 2020 (43% homicides).5 And, as with guns, we are far worse than our OECD peers, as detailed in a recent NYT article.

There are basic steps we could take as a country to improve this: speed limits, vehicle safety requirements, infrastructure improvements, traffic enforcement, public awareness.

In short, if we cared about car deaths, there are easier solutions than AV.

Save time, not lives?

Rather, the argument the AV companies could make is that they’ll save us time. We don’t like to say it, but we make tradeoffs between acute pain of human deaths and broader economic benefits. The pandemic seemed like the first time we acknowledged/debated/punched flight attendants over it as a country.6

We know we could lower speed limits and save lives, but we don’t want the inconvenience: less time for earning money (or spending time with family) and higher cost for everything we buy.

So – hypothetically, as I am not advocating for this argument – what is the economic potential not to the AV companies but to society?

AV testing has focused largely on urban robotaxis because that is how the companies will make money. But that may not be the most important service to society.

Let’s assume that we can’t solve those edge cases.7 But we can reliably replace simpler scenarios with only rare human intervention and a “tolerable” number of incremental deaths. Since most issues cited are urban-related (turning, pedestrians, cyclists), I’ll approximate this with highway and rural miles, what I’ll call: SaferMiles™.

In 2019, Americans drove 3.3 TRILLION miles. Of those, 17.7% were interstate urban and 30.2% were rural. Since we care about time, not miles, I’ll assume those were driven at 2x the speed.

Those SaferMiles, would therefore constitute 28% of our time spent driving.

With Americans driving 70B hours per year, that is 19.3 billion hours Americans would no longer spend driving!

Show me the (Waymo-scale) money!

How would people spend this time saved? COVID gives us a great example. UChicago estimated Americans saved 60M hours daily by not commuting8; 44% of that time was reallocated to working a primary or secondary job.9

We’ll use this to approximate increased productivity. Here is the math:

19.3B hours saved x 44% used for incremental work = 8.5B hours of incremental work

In wages: 8.5B hours of incremental work x $33 avg. US wage = $280.8B incr. earnings

In GDP: 8.5B hours x $68 GDP per hour = $578.7B incremental US GDP

That is a $846 increase in income per capita (1.2%) and 2.5% increase in GDP.10

It doesn’t seem like much, but consider the US COVID relief checks ($817B) were $3,200 per adult and the entire new infrastructure package ($550B) is expected to boost GDP by just 0.6% next year and 0.2% in 2024.

And the “non-productive” time? Would people call their parents/kids? Write screenplays (or newsletters!)? Learn a new language? I have no idea how to measure that impact. Or maybe we’d just increase the 2.5 hours we spend daily on social media.

Broader Significance

Back to trashing AV. Maybe it all works out, and it becomes a fantastically-successful investment. But for now, you and I are still driving ourselves around, despite the billions spent.

It’s amazing given all the headlines about tech busts that this hasn’t been bigger news (until Businessweek and I wrote about it) and that there hasn’t been more scrutiny or accountability.

It is likely because this spend is spread across a bunch of companies and there haven’t been high-profile collapses. The AV-dedicated companies are not (yet) consumer companies. And the rest are massive companies making secondary investments that aren’t broken out in their filings. Until recently, the potential for TAM expansion may have mattered more to investors than the cost.

But $100B is an insane/unprecedented/silly amount of money to still be pre-revenue, let alone profitable. (How much did Henry Ford burn?) Even if they can make it work – how long will it take to prove this was a worthwhile investment? And what else could they have spent the money on?

They could have created Airbnb 13x over!11 Let alone all the “old companies”: Disney, GE, Nike, etc. What an impact that money could have had on the world. Some other disturbing data points for what you could do with this money:

Defend democracy – The US has sent just $19B to Ukraine in 2022.

Build a text-based social network that isn’t overrun with/led by white nationalists – Twitter raised only $13B in funding (and is not profitable).

Feed millions – The World Food Program raised <$10B in 2021.

A GPS to navigate where we go from here

As discussed in last week’s post about FTX, Twitter, and Disney – investors ultimately set the guardrails.

Looking back on the past decade of cash-burning startups, what did VC get right? That is, what were business models that needed huge scale to be profitable and required the backing of billions from patient investors? Uber and DoorDash stand out.

What were the businesses that should have been abandoned but there was too much money available? WeWork, AV, everything blockchain(??) are at the top of the list. Going into this (potentially/likely/certainly) darker period for fundraising, what businesses won’t get backed? Will investors get it right?

FWIW, profitability may also not be the best KPI for positive impact on the world:

Neither the report nor the article addresses whether some of this investment is transferable to other technologies. Nearly half was spent on semiconductors including 5,000 patents. A large share was spent on higher-quality maps, RADAR, and LIDAR.

Chafkin notes that Levandowski may not be objective, given he was publicly expelled from the AV world. He left Google for Uber. Google sued Uber for $1.8B; it got $250M and another $179M from Levandowski. He was convicted for trade secrets theft and sentenced to 18 months in federal prison but pardoned by Trump at the behest of Peter Thiel (who didn’t know Andy but fucking hates Google). Interest in a future post about how Thiel spends his time and money (Gawker, Trump, Blake Masters)?

For NPV, I use MS’s 2% terminal growth and 10% WACC for consistency both with their original forecast and current Alphabet model. For IRR, I assume $7B burn split evenly 2009-2022 and 15x multiple in 2055.

I like Andreessen’s general point – our regulation of new technology was very different a century ago. However, the first cars actually weren’t very dangerous because there were so few of them and they moved so slowly. We don’t know deaths per mile back then, but as a measure of the public’s tolerance for casualties: deaths per capita wouldn’t reach today’s levels until 1919. The reaction to tech now is arguably justifiably more defensive because its adoption is more rapid (except in the case of AV). For example, every American got iPhones and Facebook a lot faster than our great-grandparents got cars. I wish we’d understood their risks earlier.

It might be because individual deaths – whether vehicle or gun – don’t make headlines. We only pay attention to mass deaths, which are far more common with guns than cars.

Subway platform barriers are another painful example of cost vs. lives decisions. There were several tragic deaths in NYC recently when people fell or were pushed onto tracks. But an MTA assessment found it would cost $7B to build barriers at even ¼ of the stations and another $120M/annually to maintain them. Presumably because the pain is rare and limited to those families, city residents would (seemingly) prefer to spend the money on schools and hospitals (and a 2.4-acre floating island in the Hudson River).

There have been similar “perfect is the enemy of the good” arguments about electric vehicles vs. hybrids. A recent NYT column eloquently argued that we should stop searching for EVs with a 500mi range and instant charging because 95% of car trips are <30 miles and could be solved with hybrids. (Climate advocates, who generally believe we need to reach net zero to stop global warming, would disagree.)

For what it’s worth, driver-assist systems are also effective and reduce rear-ending by 50%. But that does not help the productivity outcome we’re looking at here!

We could also replace driving time with better public transportation (buses, trains) or private transportation (car pooling, company buses), but this newsletter was long enough already.

I’m skeptical about people’s self-reported hours worked. If this survey were accurate, our incremental work hours (6.6B) would’ve been very close to my AV figures. I don’t think any economists saw that impact. There are certainly diminishing returns on working more hours (argument for 5 hour days or 4 day weeks) and were some offsetting time/distraction costs from COVID. There were other reports (including JP Morgan) that people were producing less work during the pandemic. But there were other factors (mainly that WFH is just less productive) that may not apply to my AV argument.

Airbnb burn based only on public information. We lost $4.9B 2020-2021, most of that being the one-time impact of RSUs vesting when we went public. We lost $761M 2017-2019, so I conservatively assume we lost $2B in the preceding nine years.

"But $100B is an insane/unprecedented/silly amount of money to still be pre-revenue, let alone profitable."

This... isn't obvious to me. Doesn't your downside DCF analysis alone prove that this isn't correct? What is the amount of capital that has gone into pre-revenue AI investment? How much went into the initial CleanTech boom? If there's a plausible, conceivable upside case (which even now it feels like there is), then is it really silly?